How to be a pessimistic organiser for successful events?

This post was originally written for the Software Sustainability Institute’s blog series. More blogs from me on SSI page can be seen here

Let me start by saying that I am a positive person (generally speaking!). If you tell me about a disaster, I will try to find something positive in it. Having made that disclaimer, I can now safely say that I am a bit pessimistic too. Therefore, no matter how positive I am about my training and outreach events as a community manager, I am ready to fight the disaster that hasn’t occurred yet.

I have organised a number of events ranging from formal conferences, semi-formal training courses, to informal social meetings. In the last three years, I have become very comfortable with the kind of work that goes into organising such events. I have also become quite aware of the fact that my events will face unexpected threats even though I have planned everything well. This is where I want to use the term “pessimistic organiser”: someone who organises an event assuming that some disasters may appear.

Important aspect of planning an event, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3368395

One of the first tasks in my current job, while I was still recovering from my PhD life, was to host a week-long bioinformatics workshop for a group of 40 people that included new pre-docs and senior researchers from a European PhD training network. I had never organised any international event before, and this was the first project where I had a chance to lead and execute an event as the main organiser. This included designing and delivering the protein informatics workshop, organising travel and accommodation of everyone, handling the budget, choosing and booking locations for all the events, hosting an official dinner, finalising menus, coordinating with all the members and trainers involved, and everything in between. To my surprise, starting from the day that everyone arrived until everyone left, this event faced a number of challenging surprises. Did I expect them? No! I wasn’t a pessimistic organiser yet.

I had no contingency plan for what I would do if something went wrong. I was only excited about ticking the boxes on my task list and didn’t take unexpected threats into account. Things did go wrong. For example, a new student showed up without a registration, a senior researcher decided to not show up on the first day that led to automatic cancellation of their hotel booking, one department was on vacation on the day they were supposed to host a tour to their facility, and the committee meeting went on one hour longer than scheduled and I wasn’t sure if I had the authority to interrupt them. These were exceptional situations that I couldn’t have predicted. However, I could have worked on my risk-management plan to already think of the challenges and put some possible solutions in place.

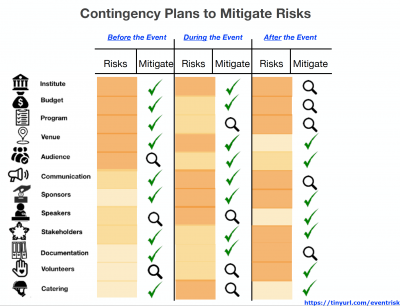

Prioritising tasks and risks to address (green tick mark) and monitor (magnifying glass) before, during, and after an event, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3368395

So… that was exciting, and it was a great learning experience too. Instead of making a big deal about any of these, my supervisor Toby Gibson told me to always remember that “things will go wrong, and that is alright”, and he was right. These minor challenges did not affect the overall success of the event.

I have come a long way since then. In the last year alone, I have chaired three international scientific conferences. I have organised and taught in a number of workshops, and have hosted various informal and formal outreach event series. Many of these events faced logistical problems (no show, low budget, and high demand), technical problems (no internet, lost packages, unsuitable venue, and projector failure) and natural disasters such as flood (Rome, Nov 2018) and earthquake (La Plata, Dec 2018). In the process of organising these, I have identified the important aspects of planning a scientific event. Furthermore, I have also created comprehensive lists of responsibilities that appear in the different stages of event organisation, risk assessment, task prioritisation, and risk mitigation.

Adapted from an Illustration from Barron & Barron Project Management for Scientists and Engineers.

Few of my top tips for planning an event as a pessimistic organiser are the following:

Involve the different stakeholders from the beginning while maintaining clear communication, setting the right expectations, developing strategies and sticking to a defined timeline. Store all information including policies, checklists, meeting minutes, and delegated tasks in a common (possibly shared) location. Transfer risks to the experts or external vendors for high-profile events (AV setup, budget, catering, transportation, etc.). Document past events. Our history can help us identify the possible challenges and their solutions, and reveal triggers for specific risks that may have appeared before.

A complete note on this topic and a related presentation are available online under the title Risk Management for your (scientific) events (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3368395) and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use this resource in your own workflow and provide your feedback to further improve it.

If I may ignore the topic of this post for a moment and point to a single aspect of creating a successful event, it won’t be pessimism. It would be ‘designing’ a welcoming and inclusive environment consciously while valuing everyone’s time and participation. If we can take care of this one thing, nobody will care about the minor glitches that are bound to occur (and often can be solved with good coffees and cakes!).